JACOB JR, MY JEWISH WORLD. AFTER THE HOLOCAUST

Monday, Sivan 5, 5776. June 13, 2016.

Shalom! World.

The idea that Judaism, could be a religion was near the faith of the modern nation-state. So is good for the Jews as well as for everyone. For this reason, the claim that Judaism is a religion implies a certain faith in the modern nation-state and the modern world.

In the aftermath of the Holocaust, a number of Jewish thinkers reevaluate this faith in the promises of modernity and particularly those of the modern nation-state. After all, the granting of full political rights to Jews in Europe culminated not in new political societies based in reason as well as committed to freedom and equality but instead in the systematic extermination of six million Jews. So, how the Holocaustmay alter arguments about the nature of Judaism and modernity by examining two seemingly unrelated streams of thought: religious Zionism, and late twentieth-century French philosophy.

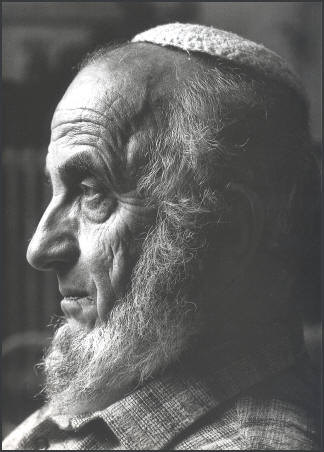

Despite their profound differences, religious Zionists, such as Emil Fackenheim (1916-2003) and Zvi Yehudah Kook (1891-1982), and a number of French Jewish philosophers, such Emmanuel Levinas (1906-1996), share the claim that Judaism is precisely that which transcends mundane politics in order to bring about the possiblity of a redemptive world order that stands beyond the modern nation-state. Notwithstanding this shared premise, however, religious Zionists since Fackenheim and Kook along with Jewsih thought inspired by Levinas often arrive at radically opposing political conclusions. For religious Zionists, the land of Israel, the state of Israel, and the Jewish people are literally part of a final redemption. In contrast, for the followers of Levinas, the state of Israel and the Jewish people are universal models or representatives of ethics. This deep divide between schools of thought nevertheless masks a profound similarity. Both of these schools respond to the Nazi genocide and what they claim are the false promises of modernity by rejecting the modern liberal distinction between religion and politics. In turn, both schools of thought attempt to reinsert religion into politics. In exploring the ideas of these thinkers, we will see after the Holocaust, the contention that Jewish religion does not interfere with the state gives way to the assertion that Jewish religion, and only Jewish religion, can give the state its meaning.

Mendelssohn, invented the idea that Judaism is a religion in order to make room for the emergence of the modern nation-state, but the Holocaust proved that he was wrong.

Fackenheim was born in Halle, Germany. He was a student of philosophy and close to finishing his training to become rabbi when, in November 1938, the nazis staged a ferocious riot against the Jews. Fackenheim was arrested and taken to Sachsenhausen, a concentration camp, and held for several months. After he was finally released on the condition that he leave Germany, he traveled to Sweden, where he was quickly deported to Canada before gaining asylum. Eventually, he became a professor of philosophy at the University of Toronto and subsequently at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The philosophical, theological, and political challenges of the Holocaust are the central themes of Fackenheim's profilic work.

According to Fackenheim, the Holocaust is at once incomprehensible and unique. The Nazis tried to extinguish the Jewish people not for what they believed or did but rather simply for they were. It is human reason's recognition of this incomprehensibility that accounts, in Fackenheim's view, for the Holocaust's uniqueness. How, then, should a jew respond to the Holocaust? For Fackenheim, the burden of answering this question is almost unbearable. "How dare a Jewish parent crush his child's innocence with the knowledge that his uncle or grandfather was denied life because of his Jewishness? And how dare he not burden him with this knowledge? The conflict is inescapable."

Shalom! Aleichem.

Mendelssohn, invented the idea that Judaism is a religion in order to make room for the emergence of the modern nation-state, but the Holocaust proved that he was wrong.

|

| KONZENTRATIONSLAGER SACHSENHAUSEN/GERMANY |

According to Fackenheim, the Holocaust is at once incomprehensible and unique. The Nazis tried to extinguish the Jewish people not for what they believed or did but rather simply for they were. It is human reason's recognition of this incomprehensibility that accounts, in Fackenheim's view, for the Holocaust's uniqueness. How, then, should a jew respond to the Holocaust? For Fackenheim, the burden of answering this question is almost unbearable. "How dare a Jewish parent crush his child's innocence with the knowledge that his uncle or grandfather was denied life because of his Jewishness? And how dare he not burden him with this knowledge? The conflict is inescapable."

Shalom! Aleichem.

Suporte cultural: Jacob Jr. B.A.C.E., avec L'Integration d'Association avec Israel et dans le Monde/Cz.

Comments

Post a Comment